Cover Up at Hawkshead Pumping Station? Illegal Sewage Dumping in the Windermere Catchment

Following our previous investigation—which revealed that 2024 saw a record 140 days with illegal sewage dumping taking place around Windermere—we’ve taken a closer look at how the Environment Agency (EA) is failing to hold United Utilities (UU) accountable. This report focuses specifically on UU picking and choosing what illegal discharges at Hawkshead Pumping Station they wanted to report (hereafter HHPS).

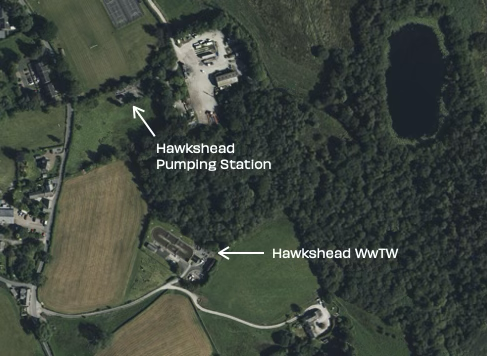

Figure 1: Hawkshead Pumping Station & WwTW in the Windermere catchment.

HHPS is the terminal pumping station responsible for transferring sewage from the village of Hawkshead to the wastewater treatment works of the same name. It is one of several sites around Windermere that discharges untreated sewage into the environment—and it is a major offender.

Since 2020, this site has dumped untreated sewage for over 10,000 hours. Crucially, it is also a significant source of illegal spills.Analysis by Professor Peter Hammond of Windrush Against Sewage Pollution reveals that HHPS is the worst-performing site in the entire catchment, totalling 280 days with illegal spilling since 2020.

HHPS is a key site for Save Windermere, not only because it is a major spiller and thus a significant contributor to the lake’s pollution, but also because it discharges into Esthwaite Water, the most protected freshwater site in the catchment. Esthwaite is both a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a designated RAMSAR site. These designations are meant to confer international conservation significance, and it should be protected as such, but sadly the site is being actively exploited by the water company.

We want to note that, while we reference staff members selectively or not reporting spills to the EA, we are in no way placing blame on them. Staff on the ground at water companies are often left to deal with poor management, limited resources, and chronic underinvestment, and are frequently left to pick up the pieces.

Our evidence is directed at the top levels of the organisation, as it is fundamentally at this level that decisions are made. The general public should be aware of the conditions under which water company staff are working and should treat them with respect.

Illegal Spills at Hawkshead Pumping Station

Beyond simply focussing on the number of illegal spills at HHPS, we want to explore a series of specific pollution events—some of which United Utilities (UU) self-reported to the Environment Agency (EA), and others where UU was clearly aware of what was happening but, as far as we can see, failed to report it to the regulator.

Pollution incidents are significant, not only because of the environmental harm they caused to Esthwaite Water and Windermere, but also because they feed into the water companies’ Environmental Performance Assessments (EPAs). These assessments are used by OFWAT, the financial regulator, to determine whether companies should be allowed to increase customer bills, and by how much, based on the number of incidents and whether performance targets are being met.

It is the EA’s responsibility to investigate these incidents and audit spill data, but as we will show below, they are failing to do either sufficiently. This failure not only allows repeated breaches to go unpunished—it enables water companies to manipulate performance metrics while continuing to pollute some of England’s most precious ecosystems.

What Makes a Sewage Discharge Illegal?

Before we get into the specific pollution incidents, here’s a quick reminder of what constitutes illegal spilling. There are two main types: early and dry.

Early illegal spilling occurs when sewage is discharged before a treatment works or pumping station has reached its legally permitted flow-to-full-treatment (FTFT) rate, also known as pass forward flow (PFF). Sewage treatment plants are required to process a certain volume of sewage (measured in litres per second) before any untreated overflow can be released. Discharging before reaching this threshold is illegal—unless explicitly permitted under emergency conditions (more on this later!)

Dry weather spilling is more straightforward: if it hasn’t rained in the past 24 hours and the site is dumping untreated sewage into the environment, it’s illegal.

By cross-referencing flow data (the amount of sewage going to the sewage treatment works) with EDM logs (which track the number of discharges and their duration) and rainfall, Professor Peter Hammond of Windrush Against Sewage Pollution (WASP) uncovers both the number of illegal discharges and their duration.

At Hawkshead Pumping Station, the pass forward flow threshold is 14 litres per second. If the site is discharging without meeting this rate, and United Utilities cannot provide evidence that it falls within permit exceptions, then it is an illegal spill.

Illegal spilling isn’t a technical grey area to manoeuvre or regulatory ambiguity, they are clear breaches of environmental law. And when they occur in places like Esthwaite Water, the consequences are not abstract. They are destructive, and, above all, preventable by sufficient investment.

Save Windermere and WASP Investigation

We began our investigation by requesting all self-reported incidents from United Utilities (UU) to the Environment Agency (EA). This allowed us to identify when incidents occurred and examine the reasons UU gave for each one.

We specifically requested the following from the Environment Agency:

“All self-reported incidents submitted by United Utilities in the Windermere catchment from the start of the year [2024] until the current date [6 June]. Please include initial NIRS reports, final EA investigations, 72-hour reports from United Utilities, and all supplementary evidence provided by UU for each incident.”

NB. Given the precise nature of our request, we have assumed that any incidents referenced in this report—aside from those that were clearly self-reported by United Utilities—were not disclosed to the Environment Agency. If they were, the onus is on the EA to explain why that information was not shared with us.

The National Incident Reporting System (NIRS) provides the initial evidence submitted when a pollution event is declared. It can also include a follow-up report from the water company, typically completed within 72 hours. This follow-up is the company’s opportunity to present supporting evidence to the Environment Agency.

Once we received this information, our next step was to request detailed site data from United Utilities.

Sewage infrastructure collects a wide range of real-time data that can reveal a lot about what is happening at a site. This goes beyond just Event Duration Monitoring (EDM) data. It also includes:

Telemetry data: Real-time updates on site activity, such as whether an emergency is occurring, if the site is spilling, whether operator attendance is required, which pumps are operational, and more.

Wet-well data: Indicates how much of the site’s storage capacity is in use. High levels triggering alarms can signal that a spill is imminent or already happening.

Flow data: Measures how much sewage is being pumped from Hawkshead Pumping Station to the Hawkshead Wastewater Treatment Works. This is crucial in determining whether spills are legal or illegal.

We also requested any data logged manually by staff, such as site diaries or logbooks, which record when operators were on site, what they observed, and any actions taken or communicated to colleagues.

As expected, United Utilities was not forthcoming with this data and initially refused our request. As we’ll demonstrate below, they even attempted to conceal critical evidence showing they knew the site was non-compliant, inappropriately redacting key information. The information was only released after the Information Commissioner intervened, following our explanation of why UU was misinterpreting the law.

That the release of critical evidence required intervention from the Information Commissioner shows just how far United Utilities will go to avoid transparency, and just how weak current regulatory enforcement truly is.

January 2024

Figure 2: Prof Peter Hammond’s Analysis of Illegal Spilling at Hawkshead Pumping Station in January 2024

As part of this investigation’s scope, the first signs of issues at HHPS appeared in United Utilities’ data at the start of 2024. We’re using this example to introduce Professor Hammond’s graphs so you can interpret the findings for yourself. These are produced using UU’s own data.

The X-axis shows the flow rate being sent to the Wastewater Treatment Works (WwTW), in litres per second.

The Y-axis is the date or time.

The black line represents EDM (Event Duration Monitoring) data—i.e. when the site is spilling untreated sewage into the environment.

The brown line shows the volume of the wet-well at the site—i.e. how much storage is being used.

The blue line is the flow rate.

The green line indicates rainfall, measured in millimetres.

The red diamonds mark United Utilities’ logged staff attendance at the site.

The purple line denotes a specific telemetry alarm signal, which suggests direct intervention from United Utilities.

Professor Hammond uses the black line to represent moments when the EDM monitor is triggered and the site is spilling. He places this line at the consented pass forward flow rate. If the blue line (actual flow) is above it, the site is complying with its permit. If the blue line falls below the black line while spills are occurring (i.e. when the black line is present), this indicates an illegal discharge. Where the black line continues for several days, or even weeks, this isn’t an error. Spills can persist uninterrupted for extended periods.

Figure 3: United Utilities Log Book Entry for 2 January 2024, obtained via EIR, showing that HHPS was not meeting its PFF threshold of 14 l/s, but confirming that the site was spilling.

We want to highlight two key points in the January data to help illustrate how to interpret this analysis:

The data shows the site was spilling illegally from January 1st to 5th, and again from the 20th to the 30th. There was also a brief illegal spill from the 16th into the 17th.

United Utilities were on site on several days during this period and noted that the site was not meeting its flow-to-full-treatment threshold, but as far as we can see, did not report it to the Environment Agency. One site diary entry records that the pass forward flow (PFF) was just 11.6 l/s and the site was actively spilling (Figure 3).

21st February 2024

On 21st February 2024, United Utilities self-reported the first pollution incident in our investigation timeline at HHPS to the Environment Agency:

“During daily checks on Wednesday 21st February 2024 it was noticed the Hawkshead Pumping Station was found to be pumping around 10l/s. Hawkshead permit is 14l/s.”.

They report that they were first notified of the event at 8:00am and were on site at 11:35am.

They say they inspected the pumps and found no issues. The non-return valves were also inspected and found to be functioning correctly. The issue was said to have been resolved by flushing the rising main, as a “quantity of thick effluent was witnessed passing to the WwTW.” This release of sludge was reported to have restored pumping to approximately 15 l/s, bringing the site back into compliance.

As part of their 72-hour follow-up report, UU provided the EA with photographs of samples taken and a screenshot of the wet-well graph from the site.

This is where our investigation begins.

The first question we ask is: what evidence was not included in United Utilities’ self-report to the Environment Agency? Notably, there was no detailed data provided to explain the cause of the spill.

What we found in our investigation

As above, Figure 4 shows Professor Hammond’s analysis of the wet-well data, flow data, EDM logs, telemetry records, and site logbooks provided by United Utilities. We also supplemented this with rainfall data.

Figure 4: Prof Peter Hammond’s Analysis of Illegal Spilling at Hawkshead Pumping Station in February 2024

What this data clearly shows:

United Utilities’ logbooks confirm that they were aware the site was spilling illegally as early as 16th February—five days before it was reported to the Environment Agency.

UU returned on 20th February and were still aware of the ongoing non-compliance.

The incident was finally reported to the EA on 21st February.

Despite claims that the issue was resolved, the site continued to spill illegally and intermittently until 26th February, when discharges finally ceased.

In total, the site spilled illegally for 16 days. Interventions to flush the rising main clearly failed to fix the problem.

Figure 5: Redacted vs. Unredacted Logbook Entries (16 February 2024) showing an attempt to cover up the fact that staff had recorded non-compliance on the 16th February, five days before it was reported to the Environment Agency.

When we first requested information on this incident, United Utilities was highly obstructive. They initially redacted key logbook entries—specifically those confirming that staff had identified non-compliance on 16th February. UU claimed the redactions were due to the inclusion of “personal information”, but after we challenged this, with intervention from the Information Commissioner, the un-redacted entries were released, exposing their prior knowledge of non compliance.

It’s important to note that in this—and subsequent—incidents, United Utilities’ permit allows for emergency sewage discharge via the designated outlet, but only under strict conditions. An emergency is defined as:

“the period when the sewage pumping station is inoperative as a result of one or more of the following, which is not due to the act or default of the operator, its agents, representatives, officers, employees or servants: electrical power failure; mechanical breakdown of duty and standby pumps; rising main failure; blockage of the downstream sewer.”

In this case, United Utilities stated:

“Site authorised to spill in an emergency due to a blockage in the downstream sewer. The thick effluent in the downstream sewer was cleared, allowing the pumps to pump the required flow. Therefore, this has been assessed as a compliant spill which caused a Cat 3 incident.”

By attributing the spill to a partial blockage, UU positioned it as falling within the permit’s emergency exemption. However, the crucial point to us is this: no evidence was provided to support the claim—and the site was spilling illegally both before the incident was reported to the EA and after the blockage was supposedly cleared.

Finally, in relation to the February 21st self report, they state that:

“A complete clean is planned in using contractors for the pumping station to prevent a repeat of the situation again.”

Yet just 20 days later, another incident was reported to the Environment Agency, citing almost exactly the same issue. Between these two self-reported incidents, another illegal spill began on 1st March. A UU operator was once again on-site and noted that it wasn’t meeting the pass-forward flow rate. However, this was not reported to the EA.

This pattern of known non-compliance going unreported is not a one-off. It’s part of a consistent failure by United Utilities to meet its legal obligations, and by the Environment Agency to enforce them.

13th March 2024

Figure 6: Prof Peter Hammond’s Analysis of Illegal Spilling at Hawkshead Pumping Station in March 2024

Let’s move on to the next incident that caught our attention. On 13th March 2024, United Utilities visited HHPS at 13:15 during routine maintenance rounds. They found the site discharging untreated sewage before meeting its permitted pass-forward flow rate. At 13:22, they reported the incident to the EA, stating that only 10.5 l/s was being passed forward—below the required 14 l/s. They also confirmed that the remaining 3.5 l/s was being discharged directly into the environment.

UU told the EA they believed the issue was caused by a partial blockage. After the rising main was flushed by an external contractor, flows reportedly returned to permitted levels at around 21:20.

By our calculations, if the site was discharging 3.5 l/s into the environment and this continued for the full 8-hour window between the report being made at 13:15 and the flows returning to normal at 21:20, an estimated 101,850 litres of untreated sewage was released into a designated RAMSAR and Site of Special Scientific Interest.

United Utilities claimed this was a Category 4 pollution incident, meaning no environmental harm had been caused and, as such, it would not contribute towards their Environmental Performance Assessment (EPA) score. In this instance, the only evidence provided by UU to the EA was a series of photographs of samples taken at the time of the event.

What stands out is that, following a separate incident at HHPS on 4th April, UU voluntarily submitted screenshots of flow and wet-well data to support their investigation. We won’t examine that case further, as the telemetry data does appear to confirm their claim that a power surge tripped one of the pumps. However, what’s notable is this: both UU and the EA know exactly what data is available at this site—yet appear highly selective in what they provide, or request, depending on the narrative they want to support.

What we found in our investigation

This is where the story gets even more revealing. UU’s data shows that the site actually began spilling illegally at around 05:48am on 13th March, more than seven hours before United Utilities arrived. UU was very particular with its wording in the initial report to the Environment Agency, stating:

’On Wednesday 13th March 2024 around 13:05, whilst visiting Hawkshead wastewater pumping station, it was found that the flow to the wastewater treatment works was reduced.’

What immediately stood out was that UU only declared when they discovered the spill, not when it actually began. Nowhere in the initial report, investigation, 72-hour follow-up, or supporting evidence do they acknowledge the start time of the non-compliant discharge.

Figure 7: Prof Peter Hammond’s Analysis of Illegal Spilling at Hawkshead Pumping Station from 13-14 March 2024, showing that the site began spilling illegally at around 05:48am.

If the site continued discharging at 3.5 litres per second during those seven unreported hours, then by our calculations, approximately 190,050 litres of untreated sewage would have entered Esthwaite Water.

But it doesn’t stop there.

United Utilities claimed the issue was caused by a partial blockage in the sewer, which they said was resolved by 21:20. Around that time, the data does show the flow rising to meet the required pass-forward rate—around 10pm on the 13th. However, the site began illegally spilling intermittently again just a few hours later, in the early hours of 14th March, despite UU’s claim that the issue had been resolved.

In reality, United Utilities’ own data shows the site spilled for 13 consecutive days from 13th to 25th March, with intermittent illegal discharges occurring throughout, particularly between the 13th and 19th. Yet after the initial report to the Environment Agency, UU did not report any of the subsequent non-compliant spilling.

Figure 8: An empty log book, showing that United Utilities made no notes on what was happening at the site on the day this illegal spill was reported, despite being present.

Despite being on site for routine rounds on 13th March when this incident was reported, United Utilities made no logbook entries documenting what was happening at the site. For a site releasing tens of thousands of litres of untreated sewage into a protected lake, the absence of any written record is not only suspicious, it’s damning.

The EA Investigation

So what did the EA do in response to this pollution event?

They visited the site and sampled the river. After undertaking their ‘investigation’, they stated:

“We agree with UU assessment of a CICS Cat 4 actual impact. The discharge was occurring whilst only 11 l/s was being passed forward to Hawkshead WwTW, 3 l/s short of the requirement to pass forward 14 l/s whilst discharging. The discharge was non-compliant with condition 2.3.2.a of the discharge permit for the site, 017380284. See Section 4b for action.”

We had immediate concerns about the Environment Agency’s approach. They didn’t access the pumping station, and, most importantly, they didn’t request any data at all. Yet despite this, they concluded that there was no environmental impact and that the issue had been resolved.

To remind you, Esthwaite Water is a SSSI and a RAMSAR site—i.e. a highly protected, environmentally significant site of international importance. Given our estimate that over 100,000 litres of untreated sewage were discharged into this lake, we do not believe this incident can reasonably be classified as having “no environmental impact.”

So, we challenged the EA:

“We believe 101,850 litres was released from the moment the incident was noticed to when it was resolved. However, we believe it was potentially longer than reported. But there is no flow data, EDM data, telemetry data or wet well level data provided by UU—nor, most importantly, was it requested by the Environment Agency. Additionally, there is no evidence to support the claim of a blockage. As far as I can tell, it was classed as a category 4 and the investigation was closed. The discharge was released into an SSSI and RAMSAR site. This should not be a CAT 4 with no impact. But even if it was a CAT 3, the EA has failed to assess this incident sufficiently.”

The EA responded:

“We have reviewed our response to this incident at Hawkshead Pumping Station on 13 March 2024 and concluded that we did not categorise this incident correctly. We have changed this to a category 3 incident because we do not agree with United Utilities’ assessment of ‘no impact’. Our category 3 assessment is because: the flow rate of sewage entering the watercourse was not a ‘very low flow discharge’, the evidence gathered by my site controller at the time including readings of ammonia and dissolved oxygen in the watercourse, and confirmation that it was raining when the pumping station was discharging.”

The EA’s eventual reclassification of the incident as Category 3 is a start—but it’s nowhere near enough. It still avoids the fundamental question: why did the EA accept a flawed, incomplete report from a company with a financial interest in minimising the impact? And why is this still happening?

Nor does it address the central issue: the legality of what happened at Hawkshead Pumping Station on 13 March, or how long the site was spilling illegally.

Total Illegal Spilling

Figure 9: Prof Peter Hammond’s Analysis of Illegal Spilling at Hawkshead Pumping Station for full year 2024.

As noted at the start of this blog, Hawkshead Pumping Station is a major source of illegal sewage discharges. In 2024 alone, there were 67 days on which illegal spilling occurred. These discharges took place across the year, making HHPS a central focus of our campaign.

This consistent pattern reflects a lack of capacity at the pumping station, driven by chronic underinvestment. The site’s permit has not been updated since 2011, so it is not unreasonable to suggest that this has been happening for over a decade.

In other words, what’s happening at HHPS may be just the visible tip of a much longer, deeper history of unchecked pollution and regulatory failure.

Final Thoughts

What we’ve shown in this report makes one thing clear: it is unacceptable that the Environment Agency has yet to take meaningful action over what is happening in and around Windermere.

This is yet another example of the regulator’s flawed and passive approach to environmental protection. There is no professional curiosity, no scrutiny of the data, and no willingness to challenge the water companies. They avoid rocking the boat, ultimately leaving out lake to be exploited by a £7 billion corporate predator while the regulator looks the other way.

Time and again, we are forced to do the work of the regulator. But we can only take it so far. It is now time for the government to intervene.

We have written to Environment Minister Steve Reed, providing all of the evidence set out in this report, and have also contacted the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP) and the Environmental Audit Committee (EAC). The government must act on this evidence and compel the regulator to do its job. That means re-evaluating each illegal spill highlighted here, and investigating all six United Utilities sites where we have identified ongoing illegal discharges in the past five years.

We do not believe individual operators on the ground should be blamed, nor is this fair. They are working within a broken system, constrained by underinvestment. If Hawkshead Pumping Station simply cannot cope, that may explain the reluctance to be transparent. But refusing to acknowledge the problem will not fix it. Until there is accountability, and until United Utilities feels pressure at the corporate level, nothing will change and no definitive action will be taken.

If the regulator fails to identify these incidents, it remains business as usual. The company will face no fines, no prosecutions and no consequences for prioritising shareholder dividends over the protection of England’s largest lake.

And make no mistake: this is not just happening in Windermere.

And it’s not just United Utilities.

This is the systemic failure of water industry privatisation.